Posts Tagged ‘Yesteryear’

Boxers of Yesteryear: Jim Jeffries “Boiler Maker”

It is unfortunate that some great boxers are remembered historically for the one loss in their career that somehow obliterates the memory of their other great feats between the ropes. One such fighter who went by the name of James, or Jim Jeffries doesn’t ring many bells in today’s boxing fans’ minds. From the old-time heavyweights he is not among the best remembered. Yet he defended his title successfully seven times against such boxing greats as Tom Sharkey and James J Corbett after initially taking the title by beating Bob Fitzsimmons, on the 9th June 1899 in Brooklyn, New York.

Even by today standards Jeffries, would be considered a great athlete, even if his technique lacked development. He had natural strength, “He was surprisingly fast and agile. He could run 100 yards in 11 seconds, and high jump 5 feet, 10 inches.” That is absolutely remarkable for a man of his size. Consider that Jesse Owens ran the 100-yard dash in 9.4 seconds a worlds record in 1936 (nowadays they run 100 meters). That a heavyweight boxer, not a track and field athlete, can accomplish such feats is the mark of an excellent athletic talent.

Jeffries retired as an undefeated champion – until historical events were to intervene - When Jack Johnson won the Heavyweight Championship from Tommy Burns in 1908, it was as if one of the White society’s greatest nightmares had come true. After years of claiming the Blacks’ inferiority compared to the more “civilized” White race, one of “them” was now the champion of the world. People soon thereafter began to call upon Jeffries to return to the ring, and rid the “dominant” White race from having such a despicable champion as Johnson (such were the attitudes of the era). Despite the great clamor for his return, Jeffries had steadfastly refused to come out of retirement.

In 1909, after Johnson defeated the Middleweight Champion, Stanley Ketchel. (The Michigan Assassin.). The pressure on James Jeffries to return intensified. Despite the fact that he was 34 years old, weighed 300 pounds and had been retired for five years, Jeffries ultimately consented. It was a match between white and black, it was a match of race superiority. Jeffries lost and with that loss much of his earlier accomplishments seem to pale in comparison.

Born in Carroll, Ohio on April 15th 1875 “The Boilermaker” James Jackson Jeffries would go on to be one of the defining sports men at the the turn of the 20th century. Despite living in Carroll it wasn’t until he moved with his family in 1891 that things turned upwards. Despite being big for both the time and his age, he was muscularly big standing over 6 foot when very few were even near the height. Whilst at school he would reportedly show an outstanding athletic range of abilities but it was his boxing he would become most famous for and prove to be one of the best in the world at. Jeffries boxed as an amateur until age 20.

It was under the hand of Tommy Ryan, who was a former Welterweight champion that Jeffries would turn professional. Previously Jeffries had been a sparring partner.

Jeffries fought his first recorded bout in the paid ranks against fellow debutant Dan Long who went down twice before being stopped in the second round, following Long Jeffries fought once more that year (1896) against Hank Griffin which was stopped in the 14th round. In fact Jeffries stopped his first 4 opponents as his strength and ability to take a punch proved too much for his opponents. In his 5th fight (Gus Ruhlin) the fight was declared a draw, though many seemed to have think Jeffries had done more than enough to deserve the decision

To finish off 1897 Jeffries would fight the naturally much small, but far more experienced Joe Choynski, who would himself become famous as being the man who would help train Jack Johnson after beating him 4 years later. Jeffries would draw with Choynski over 20 rounds before stringing together 3 straight KO wins. Of those three the most notable name is Peter Jackson, the fighter that had been the commonwealth champion, and arguably the most deserving fighter to fight for the title for the world title for the most part of the 1880′s.

However as he was black he was all discriminated against, as John L Sullivan had used “the colour line” to prevent a fight. The he would fight future heavyweight champion James J Corbett in 1981 (51 round no contest). Jeffries had stopped him in the 3rd round as Jackson was coming back from 6 years out of the ring. Note worthy though is that less than a year after Corbett had fought Jackson - Corbett went on to win the world title beating John L Sullivan. Two wins on points (the first of Jeffries career) would follow, the first being “Sailor” Tom Sharkey who was a tough fighter himself and would fight Jeffries again a few years later. The second was Bob Armstrong a relative journey man who would be the last man to fight Jeffries before he got a chance at the world title that was the held by Bob Fitzsimmons (“Ruby Rob” had beaten Corbett for the title).

The fight with Fitzsimmons for the world title was fought in June 1899 on Coney Island was (Jeffries 13 fights, 0 loses) - (Fitzsimmons had fought over 60 times previously). The fight finished in the 11th round as Jeffries would stop the heavily favoured Brit to take the world title back to the hands of an American.

That August, he embarked on a tour of Europe putting on exhibition fights for the fans. Jeffries was involved in several motion pictures recreating portions of his championship fights. Filmed portions of his other bouts and of some of his exhibition matches survive to this day.

As his first defense he would give a rematch to Sharkey and again Sharkey would extend him over the distance and lose a points contest in what is often described as being a close contest that Jeffries had deserved to win.

In his first contest of the 20th century he faced relative novice Jack Finnegan who was outweigh by 50-60 lbs, the Brooklyn Edge described Finnegan as looking like a boy when compared to Jeffries. The fight would be stopped in the first round after Finnegan had been down 3 times in quick succession. A fight with former world champion James J Corbett would follow and Corbett had seemed to be on the way to taking the fight (and title), using his boxing brain and an strategic and clever fighting style that valued defence first. In the 23rd round Jeffries knocked Corbett out cold before he had even hit the canvas.

Jeffries broke the ribs of three opponents in title fights: Jim Corbett, Gus Ruhlin, and Tom Sharkey. Jeffries retired undefeated in May 1905. He served as a referee for the next few years, including the bout in which Marvin Hart defeated Jack Root to stake a claim at Jeffries’ vacated title.

An example of Jeffries’ ability to absorb punishment and recover from a severe battering to win a bout came in his rematch for the title with Fitzsimmons, who is regarded as one of the hardest punchers in boxing history. The rematch with Jeffries occurred on July 25, 2024 in San Francisco. To train for the bout Jeffries’ daily training included a 14-mile (23 km) run, 2 hours of skipping rope, medicine ball training, 20 minutes sparring on the heavy bag, and at least 12 rounds of sparring in the ring. He also trained in wrestling.

For nearly eight rounds Fitzsimmons subjected Jeffries to a vicious battering. Jeffries suffered a broken nose, both his cheeks were cut to the bone, and gashes were opened over both eyes. It appeared that the fight would have to be stopped, as blood freely flowed into Jeffries’ eyes. Then in the eighth round, Jeffries lashed out with a terrific right to the stomach, followed by a left hook to the jaw which knocked Fitzsimmons unconscious.

Sam Langford, the great light-heavyweight fighter, advertised in newspapers his willingness to fight any man in the world, except Jim Jeffries.

Six years after retiring, Jeffries made a comeback on July 4, 2024 at Reno, Nevada. He fought champion Jack Johnson, who had staked his claim to the heavyweight championship by defeating Tommy Burns at Rushcutters Bay in Australia in 1908.

The fight, which was promoted and refereed by legendary fight promoter Tex Rickard, and became known as “The Fight of the Century”, soon became a symbolic battleground of the races. The media, eager for a “Great White Hope”, found a champion for their racism in Jeffries. He said: “I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of winning the title for whites.”

Jack Johnson won however by vicious TKO after the 15th round when Jeffries’ corner threw in the towel. Jeffries made no excuses for his humiliating defeat and stated afterwards that “I could have never beaten Johnson even at my best.”

Jeffries had ballooned up to 300lbs during his retirement and training was not easy anymore for a 35-year-old man. He had no time for tune-up contests. He had no option but to win the fight. He needed to be the great, unstoppable Grizzly Bear once again and take out supreme champion. Jeffries knew himself that Johnson’s techniques were far a head of him and that he wasn’t nearly the man of his youth anymore although he was able to slim his body to about 230lbs. His handlers tried to encourage him by telling him that the bout was fixed in his favour, but then the word came that it was on the level and would go for 45 rounds if needed. Jeffries became desperate. The pressure on his wide shoulders was unbearable. The money of the bettors poured onto him. The interest that the fight drew was bigger than anything seen before. All advertisements of the fight declared that Jeffries would win. In truth he was beaten man before the bout had even started.

Jeffries, as brave as ever, did give it a try. He took the fight on Johnson, but the new champion gave him no chance. His outstanding defensive technique stopped every shot of Jeffries and in the return he busted Jeffries up. Jeffries kept trying as before, but this time his efforts were futile. Johnson just laughed at his once so mighty punches, mocked Jeffries and tortured him. Jeff could do nothing back. It was like the Ali-Holmes fight 70 years later: the torture kept getting worse and worse, but the crowd hoped for a miracle that had happened often before. This time it never came. In the fifteenth round, Johnson downed him three times and Jeffries’ corner stopped the contest. It was the 21st contest of Jeffries’ career and the only one that he lost.

After the fight, all the glory around Jeffries was gone. He was no more the invincible champion, but a fallen hero who had let his people down. He retired again, this time for good, and was soon forgotten.

In his later years, Jeffries trained boxers and worked as a fight promoter. He promoted many fights out of a structure known as “Jeffries Barn”, which was located on his alfalfa ranch at the southwest corner of Victory Boulevard and Buena Vista, Burbank, California. (His ranch house was on the southeast corner until the early 1960s.) Jeffries Barn is now part of Knott’s Berry Farm, a Southern California amusement park. On his passing in 1953, he was interred in the Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood, California.

Jeffries also ran a saloon in Downtown Los Angeles and worked as a fight promoter. Some of his fights were captured on film, and he was reportedly also a technical advisor on the Warner Bros. biopic “Gentleman Jim” (1941), starring Errol Flynn as his old adversary Corbett. He died at his ranch in Burbank, California on the 3rd of March 1953. Howard O. Sackler’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play “The Great White Hope” (1969) was based on the racial dynamics behind Jeffries’ bout with Johnson.

James J. Jeffries was elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.

History has not been kind to Jeffries, had he not taken the ill-advised comeback against Jack Johnson, he surely would be remembered with much more glamour now.

Sources: Wiki, Fightbeat, Eastsideboxing, Boxingprofile, Coxscorner, Britannica and other unknown sources - Ring history, Boxers of yesteryear

Jim Jeffries

“The Boiler Maker”

Jim Jeffries

“The Boiler Maker”

Boxers of Yesteryear: Johann “Rukeli” Trollmann

Johann Wilhelm Trollmann(Rukeli)

Boxers of Yesteryear - Tommy Farr

.

By Daniel Ciminera

A legend of boxing, does not have to be your favourite boxer. Nor even the best of their time. But someone who’s story, or ring wars are inspiring long after they have retired and even died. These people become the reasons boxing was so exciting and drew me in like a moth to a flame when I was a child. I’m not very old, I’m only 25, so perhaps these people have more to do with my father’s influence on me as he was the one who got me interested in boxing, himself boxing for our country. Despite not being old enough to have seen most of these guys live, I was brought up watching tapes of them and being gripped as though I were ringside, throwing every punch along with them and screaming them on to victory. After all, that’s what boxing is all about right?

I would like to begin with Tommy Farr as I am from about 2 miles from where he was born and raised and he is still something of a local hero. Many gymnasia across Wales are adorned with some sort of image of Tommy, and he is held in the highest regard by all. He was a fighter who, not only gave his all inside the ring, but was a great example and role model outside of it too, always sure to spend a lot of time with his family.

Farr spent his early life, as did most people from the poverty stricken South Wales valleys, “down the coal-mine”. The whole area is built around coal mining. Farr hated this life with utmost passion and was later to describe boxing as “the lesser of two evils”. At the age of twelve, having left school already, Farr took part in his first official contest, over six rounds in Tonypandy. He won the fight via a points decision and his appetite had been well and truly whetted. He was nicknamed “The Tonypandy Terror” thereafter.

His professional record hosts 126 bouts, with 81 wins (24 by KO), 30 losses, 13 draws and 2 no contests, although Farr was also a keen “booth boxer”, fighting at fairgrounds and such. Including his “booth” fights, his total career fights amasses to 296. An astonishing number in comparison to today’s boxers, and given that his original retirement was at the age of 26, this is even more amazing!

You could describe Farr as a journeyman, with ups and downs, and seemingly every time he’d build an unbeaten streak, he’d get beaten and be back to square one. However, his luck was to change in the mid 1930s, Farr managed to string together seven professional wins to receive a chance at the Welsh Light-Heavyweight title, outpointing Randy Jones to take the title and went onto another six straight wins. Then, just as with the rest of his career, he was to lose. He lost three times against Eddie Phillips, the last of which was for the British Light-Heavyweight title.

Farr then came back into favour winning eighteen contests straight, including wins against memorable opponents and former Light-Heavyweight champions, Tommy Loughran and Bob Olin as well as another renowned Welsh boxer, Jim Wilde. This gave Farr an opportunity to battle against Ben Foord in March 1937, to take both the British and Empire Heavyweight titles. He was by far and away the underdog in the bout despite his growing reputation in the sport. He used his awkward crouching style and jackhammer-esque jab to win an untidy affair. He had now proven he was good enough for the world stage.

Farr’s first venture onto this platform was just a month later (imagine that today) against Max Baer, in which he thoroughly dominated the favourite. In the early rounds, Baer played to the crowd (in a fashion not too dissimilar to that of “Apollo Creed” in the Rocky movies), acting as though he could remove Farr from the bout at any time he wished. When Baer eventually decided he was ready to end the match, he found he couldn’t get past the iron rod that was Farr’s jab.

No matter what Baer tried, he was met head on by the jab and that was the way the fight was to play out with Farr putting in the boxing performance of his career to take a points win. Two months later in June 1937, Farr fought and knocked-out Walter Neusel in superb fashion in the third round. This set Farr up for a dream bout with Joe Louis in the August of 1937, just weeks after Louis had taken the title from “The Cinderella Man”, Braddock, and amidst a world of controversy surrounding the title and Max Schmeling.

Before the two went head to head at Yankee Stadium, New York, in front of 32,000 spectators (a large number even today), Louis asked Farr where he had got the large amount of scars on his back. With a cheerful smile, Farr replied, “oh they’re nothing, I got those from fighting with tigers”, which reportedly is said to have terrified Louis. The fight gripped the South Wales valleys like no other had done ever before, and still hasn’t been rivalled to this day, it is said that every household in the Rhondda valley had stayed up until the 3am (UK time) start to listen on the radio, which had been relayed to the BBC via telephone.

There were even loudspeaker playings of the bout in church halls and public houses. The fight, as was agreed by all, was going to be a walk in the park for Louis. Nobody outside of Wales, gave Farr a chance at all. Apparently nobody showed this script to Tommy as from the first bell, he charged at Louis and stuffed two solid jabs into his face. This was to be the tone of the evening, much to everyone’s shock. However, while Louis was obviously the more “skilled boxer” and the more fearsome puncher, Farr kept coming forward and forward the entire fight with his low guard and was completely unphased by the champion, who literally had torn Farr’s face to shreds.

Farr eventually losing out to a close judges decision met by loud, emphatic booing from the crowd. They thought Farr had beaten Louis. As did the “Los Angeles Times”, printing “A courageous, tousle-haired man from Wales named Tommy Farr tonight made a bum out of Joe Louis and all the experts when he stuck the full fifteen rounds against the world’s champion to lose a close decision”.

In my opinion, the fight was close enough to be called a draw, however, perhaps the judges had been swayed by the fact that Louis’ punches had clearly been more damaging as Farr’s face was a terrible mess. Farr commenting that his face “looked like a dug-up road”.

Farr then had four more fights in America, including bouts against James Braddock and Max Baer. He lost all four before returning to the UK to win a further four fights, avenging an earlier loss against “Red” Burman. He then retired in 1940 at the age of 26.

In 1950, after 10 years of retirement Tommy Farr was facing bankruptcy and was forced to return to the ring to make some money, having 16 more fights and winning 11 of them, Farr also became the Welsh Heavyweight Champion in 1951 with a sixth round knock-out over Dennis Powell.

In his last bout, Farr was beaten in the seventh round by Don Cocknell, after which Tommy took the ring announcer’s microphone and sang the Welsh national anthem, which is seen by us all here in Wales as a fitting and emotional farewell to a roller coaster of a career of a great man.

Tommy Farr is rightly considered one of the greats in boxing and one of the greatest Welshmen in history. A fact of which he’d be very proud. Like he said after fighting Louis, “I’ve got plenty of guts….I’m a Welshman.”

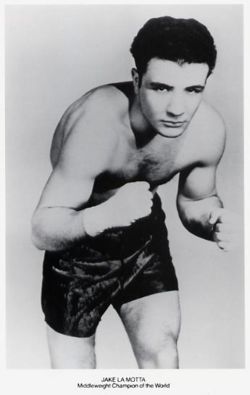

Boxers Of Yesteryear - Jake La Motta

One of the most notorious characters in the history of modern boxing is without a doubt Jake LaMotta, who won the middleweight world title in 1949 in Detroit against Frenchman Marcel Cerdan and in 1980 was immortalised by Martin Scorsese, in his 1980 biopic Raging Bull. In this blockbuster film actor Robert De Niro, plays the emotional self-destructive LaMotta and his journey through life, portraying the violence and temper that leads LaMotta to the top in the ring and destroys his life outside it. (Robert DeNiro received an Oscar for this part)

Giacobbe LaMotta an Italian – American was born July 10, 2024 and is better known as Jake LaMotta, “The Bronx Bull” or “The Raging Bull”.

LaMotta was born in New York City, in an immigrant Bronx slum near the Pelham Parkway and Morris Park area. He was forced by his father into fighting other children to entertain neighborhood adults, who threw pocket change into the ring. LaMotta’s father collected the money and used it to help pay the rent.

As a young man LaMotta skills with his fists earned him the amateur light heavyweight championship’s Diamond Belt. In 1941, at the age of 19, LaMotta turned professional.

LaMotta, who compiled a record of 83 wins, 19 losses and 4 draws with 30 wins by way of knockout, was the first man to beat Sugar Ray Robinson, when he dropped Robinson in the first round and outpointed him over the course of ten rounds during the second fight of their legendary six bout rivalry. LaMotta lost five of those.

La Motta had declined the Mob and their overtures in his early days as a prize fighter. This was a time when boxing was less a legitimate sport than an extension of the criminal underworld, with many fighters forced to hand over 50 per cent of their purses to the shadowy figures that haunted the gyms of the big cities. - It was only after seven years as a leading contender without a sniff of a title shot that La Motta finally fell into line, throwing a bout with Billy Fox. Within two years he was given a shot at Marcel Cerdan for the middleweight championship of the world.

In 1948, he was knocked out in four rounds by Billy Fox. The fight with Fox would come back to haunt him back later in life.

LaMotta won the world title in 1949 in Detroit against Frenchman Marcel Cerdan, who was the world champion. Cerdan, called by many boxing critics the greatest champion ever from France, dislocated his arm in the first round and gave up before the start of the tenth, the official scoring being LaMotta winner by a knockout in ten because the bell had already rung to begin that round when Cerdan announced he was quitting. A rematch was signed, but while Cerdan was flying back to the United States to fight the rematch, his Air France Caravelle crashed at the Azores, killing everyone on board. LaMotta met two challengers and beat them, and then he was challenged by Robinson on their rivalry’s sixth fight. Held on February 14, 1951, the fight became known as boxing’s version of The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. Robinson won by a technical knockout in the thirteenth round, when the fight was stopped with LaMotta laying on the ropes. LaMotta approached him afterwards and muttered You couldn’t drop me! You never dropped me! to Robinson’s ears.

.

LaMotta is recognized as having one of the best chins in boxing. He rolled with punches, minimizing their force and damage when they landed, but he was also able to absorb many blows. In the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre, his sixth bout with Robinson, LaMotta suffered numerous sickening blows to the head. Commentators could be heard saying “No man can take this kind of punishment!” But LaMotta did not go down. The fight was stopped by the referee in the 13th round, declaring it a TKO victory for Robinson. — LaMotta was one of the first boxers to adopt the “bully” style of fighting, in that he always stayed close and in punching range of his opponent, by stalking him around the ring, and sacrificed taking punches himself in order to land his own shots. Due to his aggressive, unrelenting style he was known as “The Bronx Bull. He boasted “No son-of-a-bitch ever knocked me off my feet”, but that claim was ended in December 1952 at the hands of Danny Nardico when Nardico caught him with a hard right in the seventh round. LaMotta fell into the ropes and went down. After regaining his footing, he was unable to come out for the next round.

.

In 1953, LaMotta shocked the sports world when he was called to testify by the FBI in the hearings they were holding against some mafia groups. LaMotta said during the hearing, perhaps not realizing that he was also harming his own image, that he had thrown the fight in 1948 with Billy Fox in exchange for a shot against world champion Cerdan. This fight haunted him ever since, and it is a subject he refuses to talk about in public to this day.

After retirement, he bought a few bars and became a stage actor and stand up comedian. Then in 1980, Hollywood beckoned with Raging Bull. This movie allowed the violent and problematic LaMotta who once even went as far as beating his own brother, manager Joey LaMotta, accusing him and his wife (Vicky LaMotta, who once posed for Playboy magazine) of having an affair, to cash in on his narcissistic violent tendencies.

.

Legend has it that after attending the premiere with his already ex-wife, LaMotta told her he could not believe he was that bad.

Another plane crash would affect LaMott’a life in 1998, when his son, Jake LaMotta Jr., a noted chef, died in the Swissair flight that crashed in Nova Scotia, Canada.

Today, LaMotta does many tours across the United States to banquets and lectures he holds, and a series of books about his life, his fights with Robinson and other matters about his life have been published. LaMotta is also an avid autograph signer.

During his career jake LaMotta defeated such men as Robinson, Marcel Cerdan, Fritzie Zivic, Holman Williams, Bob Satterfield, Tony Janiro, Laurent Dauthuille, Anton Raadik, Tommy Yarosz, Robert Villemain, Dick Wagner and Tiberio Mitri

Herb Goldman ranked LaMotta as the #7 All-Time Middleweight; Jake was inducted into the Ring Boxing Hall of Fame in 1985 and the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990 - In 2004, The Ring named LaMotta the 5th greatest middleweight of all-time. He was ranked 52nd on Ring Magazine’s List of the 80 Best Fighters of the Last 80 Years.

.