Posts Tagged ‘History’

Boxers of Yesteryear: Johann “Rukeli” Trollmann

Johann Wilhelm Trollmann(Rukeli)

Boxers of Yesteryear - Tommy Farr

.

By Daniel Ciminera

A legend of boxing, does not have to be your favourite boxer. Nor even the best of their time. But someone who’s story, or ring wars are inspiring long after they have retired and even died. These people become the reasons boxing was so exciting and drew me in like a moth to a flame when I was a child. I’m not very old, I’m only 25, so perhaps these people have more to do with my father’s influence on me as he was the one who got me interested in boxing, himself boxing for our country. Despite not being old enough to have seen most of these guys live, I was brought up watching tapes of them and being gripped as though I were ringside, throwing every punch along with them and screaming them on to victory. After all, that’s what boxing is all about right?

I would like to begin with Tommy Farr as I am from about 2 miles from where he was born and raised and he is still something of a local hero. Many gymnasia across Wales are adorned with some sort of image of Tommy, and he is held in the highest regard by all. He was a fighter who, not only gave his all inside the ring, but was a great example and role model outside of it too, always sure to spend a lot of time with his family.

Farr spent his early life, as did most people from the poverty stricken South Wales valleys, “down the coal-mine”. The whole area is built around coal mining. Farr hated this life with utmost passion and was later to describe boxing as “the lesser of two evils”. At the age of twelve, having left school already, Farr took part in his first official contest, over six rounds in Tonypandy. He won the fight via a points decision and his appetite had been well and truly whetted. He was nicknamed “The Tonypandy Terror” thereafter.

His professional record hosts 126 bouts, with 81 wins (24 by KO), 30 losses, 13 draws and 2 no contests, although Farr was also a keen “booth boxer”, fighting at fairgrounds and such. Including his “booth” fights, his total career fights amasses to 296. An astonishing number in comparison to today’s boxers, and given that his original retirement was at the age of 26, this is even more amazing!

You could describe Farr as a journeyman, with ups and downs, and seemingly every time he’d build an unbeaten streak, he’d get beaten and be back to square one. However, his luck was to change in the mid 1930s, Farr managed to string together seven professional wins to receive a chance at the Welsh Light-Heavyweight title, outpointing Randy Jones to take the title and went onto another six straight wins. Then, just as with the rest of his career, he was to lose. He lost three times against Eddie Phillips, the last of which was for the British Light-Heavyweight title.

Farr then came back into favour winning eighteen contests straight, including wins against memorable opponents and former Light-Heavyweight champions, Tommy Loughran and Bob Olin as well as another renowned Welsh boxer, Jim Wilde. This gave Farr an opportunity to battle against Ben Foord in March 1937, to take both the British and Empire Heavyweight titles. He was by far and away the underdog in the bout despite his growing reputation in the sport. He used his awkward crouching style and jackhammer-esque jab to win an untidy affair. He had now proven he was good enough for the world stage.

Farr’s first venture onto this platform was just a month later (imagine that today) against Max Baer, in which he thoroughly dominated the favourite. In the early rounds, Baer played to the crowd (in a fashion not too dissimilar to that of “Apollo Creed” in the Rocky movies), acting as though he could remove Farr from the bout at any time he wished. When Baer eventually decided he was ready to end the match, he found he couldn’t get past the iron rod that was Farr’s jab.

No matter what Baer tried, he was met head on by the jab and that was the way the fight was to play out with Farr putting in the boxing performance of his career to take a points win. Two months later in June 1937, Farr fought and knocked-out Walter Neusel in superb fashion in the third round. This set Farr up for a dream bout with Joe Louis in the August of 1937, just weeks after Louis had taken the title from “The Cinderella Man”, Braddock, and amidst a world of controversy surrounding the title and Max Schmeling.

Before the two went head to head at Yankee Stadium, New York, in front of 32,000 spectators (a large number even today), Louis asked Farr where he had got the large amount of scars on his back. With a cheerful smile, Farr replied, “oh they’re nothing, I got those from fighting with tigers”, which reportedly is said to have terrified Louis. The fight gripped the South Wales valleys like no other had done ever before, and still hasn’t been rivalled to this day, it is said that every household in the Rhondda valley had stayed up until the 3am (UK time) start to listen on the radio, which had been relayed to the BBC via telephone.

There were even loudspeaker playings of the bout in church halls and public houses. The fight, as was agreed by all, was going to be a walk in the park for Louis. Nobody outside of Wales, gave Farr a chance at all. Apparently nobody showed this script to Tommy as from the first bell, he charged at Louis and stuffed two solid jabs into his face. This was to be the tone of the evening, much to everyone’s shock. However, while Louis was obviously the more “skilled boxer” and the more fearsome puncher, Farr kept coming forward and forward the entire fight with his low guard and was completely unphased by the champion, who literally had torn Farr’s face to shreds.

Farr eventually losing out to a close judges decision met by loud, emphatic booing from the crowd. They thought Farr had beaten Louis. As did the “Los Angeles Times”, printing “A courageous, tousle-haired man from Wales named Tommy Farr tonight made a bum out of Joe Louis and all the experts when he stuck the full fifteen rounds against the world’s champion to lose a close decision”.

In my opinion, the fight was close enough to be called a draw, however, perhaps the judges had been swayed by the fact that Louis’ punches had clearly been more damaging as Farr’s face was a terrible mess. Farr commenting that his face “looked like a dug-up road”.

Farr then had four more fights in America, including bouts against James Braddock and Max Baer. He lost all four before returning to the UK to win a further four fights, avenging an earlier loss against “Red” Burman. He then retired in 1940 at the age of 26.

In 1950, after 10 years of retirement Tommy Farr was facing bankruptcy and was forced to return to the ring to make some money, having 16 more fights and winning 11 of them, Farr also became the Welsh Heavyweight Champion in 1951 with a sixth round knock-out over Dennis Powell.

In his last bout, Farr was beaten in the seventh round by Don Cocknell, after which Tommy took the ring announcer’s microphone and sang the Welsh national anthem, which is seen by us all here in Wales as a fitting and emotional farewell to a roller coaster of a career of a great man.

Tommy Farr is rightly considered one of the greats in boxing and one of the greatest Welshmen in history. A fact of which he’d be very proud. Like he said after fighting Louis, “I’ve got plenty of guts….I’m a Welshman.”

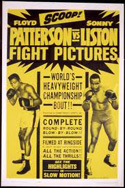

Boxers of Yesteryear - Sonny Liston

No one is sure when he was born. No one is sure when or even how he died. What can be said with certainty is Liston was one of the most imposing fighters ever to lace on boxing gloves.

Considered by many to have been a brute both inside and outside the ring, Sonny Liston seems to have been unjustly condemned to a turbulent life of trouble from the day he was born.

Charles L. “Sonny” Liston believed his birth date was May 8, 1932, but he was never sure and that led to speculation he was actually a few years older. The 24th of 25 children fathered by Tobe Liston (one of 10 with his wife Helen Baskin), Sonny came into the world in a tenant’s shack 17 miles northwest of Forrest City, Ark. “I had nothing when I was a kid but a lot of brothers and sisters, a helpless mother and a father who didn’t care about any of us,” he said (Liston). “We grew up with few clothes, no shoes, little to eat. My father worked me hard and whupped me hard.”

Helen left her husband and moved to St. Louis in 1946. Sonny ran away from home to join her. Unable to read or write, the burly teenager attempted to make a living on the streets of St. Louis. In 1950, Liston was sentenced to prison as a teenager for taking part in the robbery of a gas station. When he robbed places he always wore the same yellow t-shirt, and became known to the local police force as the “Yellow Shirt Bandit”. When he was caught running away from the gas station wearing the same yellow t-shirt, he was sentenced to 8 years in prison. His boxing talent was discovered by a Roman Catholic priest, and it was boxing that helped him get out on parole two years later, along with an endorsement from the priest. Liston never complained about prison, saying he was guaranteed 3 meals every day. On Halloween night in 1952, he was paroled. Much was later made of his being controlled by criminals. However, according to the priest who interested him in boxing, underworld figures became his management simply because they were the only ones willing to put up the necessary money.

At 6 feet ½ inch and 217 pounds, Liston had devastating punching power, an iron chin, and lightning reflexes, along with a powerful jab. He quickly destroyed all the leading heavyweight contenders.

Liston made his professional debut on September 2, 1953, knocking out Don Smith in the first round in St. Louis, where he fought his first five bouts. Considering his height, Liston had a disproportionately long reach of 84 inches (equaled only by some champs who are 6 ft 4 inches) and the largest fists in heavyweight history, 15 in (38 cm), at least until the recent appearance of 7-foot (2.13 m) Nikolay Valuev. His noticeably more muscular left arm and crushing left jab lends credence to the widely held belief that he was left-handed but utilized an orthodox stance. In his 6th bout, in Detroit, Michigan, Liston faced John Summerlin (19-1-2) on national television and won an eight-round decision. He later beat Summerlin in a rematch. The next bout was against Marty Marshall a journeyman with an extraordinarily awkward style, in the third round Marshall managed to hit Liston while he was laughing and broke his jaw. A stoic Liston finished the fight but lost the decision, this first loss did however mean that gamblers got better odds betting on him.

In 1955, he won six fights; he won five by knockouts, including a rematch with Marshall, whom he knocked out in six

rounds, after first getting knocked down himself. A rubber match with Marshall in 1956 saw him the winner by a ten-round decision, but in May of that year he injured a police officer over a parking ticket, accounts of nightsticks breaking over Liston’s skull during the arrest later aided perceptions of him as a nightmarish ‘monster’ who was impervious to punishment. He was paroled after serving six months of a nine-month sentence and prohibited from boxing during 1957, the police ordered him out of town. In 1958, he returned to boxing, winning eight fights that year. The year 1959 was a banner one for Liston: after knocking out Mike DeJohn in six he faced No. 1 challenger Cleveland Williams, a huge (for the era) fast-handed fighter who was billed as the hardest hitting heavyweight in the world. As well as the expected durability - his nose was broken in round one - and punching power, Liston showed heretofore unseen boxing skills. He nullified Williams’ best work before stopping him in the third of an ‘incredible’ contest that many thought his most impressive performance, and he rounded out the year by stopping Nino Valdez, also in three. In 1960, Liston won five more fights, including a rematch with Williams, who lasted only two rounds. He also had knockout wins over Roy Harris (one round) and top contender Zora Folley (three rounds). Elusive Eddie Machen was the only contender who was not knocked out, although Machen lost the 12-round decision overwhelmingly the match showed Liston ineffectively following a fleet footed opponent rather than cutting off the ring on him. Despite his top ranking Liston had a very long wait for the management of world heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson to consent to a match.

rounds, after first getting knocked down himself. A rubber match with Marshall in 1956 saw him the winner by a ten-round decision, but in May of that year he injured a police officer over a parking ticket, accounts of nightsticks breaking over Liston’s skull during the arrest later aided perceptions of him as a nightmarish ‘monster’ who was impervious to punishment. He was paroled after serving six months of a nine-month sentence and prohibited from boxing during 1957, the police ordered him out of town. In 1958, he returned to boxing, winning eight fights that year. The year 1959 was a banner one for Liston: after knocking out Mike DeJohn in six he faced No. 1 challenger Cleveland Williams, a huge (for the era) fast-handed fighter who was billed as the hardest hitting heavyweight in the world. As well as the expected durability - his nose was broken in round one - and punching power, Liston showed heretofore unseen boxing skills. He nullified Williams’ best work before stopping him in the third of an ‘incredible’ contest that many thought his most impressive performance, and he rounded out the year by stopping Nino Valdez, also in three. In 1960, Liston won five more fights, including a rematch with Williams, who lasted only two rounds. He also had knockout wins over Roy Harris (one round) and top contender Zora Folley (three rounds). Elusive Eddie Machen was the only contender who was not knocked out, although Machen lost the 12-round decision overwhelmingly the match showed Liston ineffectively following a fleet footed opponent rather than cutting off the ring on him. Despite his top ranking Liston had a very long wait for the management of world heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson to consent to a match.

In 1962, Floyd Patterson finally signed to meet Liston for the world title. The fight was scheduled to be held in New York, but the New York Boxing Commission denied him a license because of his criminal record. As a result, the fight was moved to Comiskey Park, Chicago, Illinois. Leading up the fight, Sonny Liston was the major betting line favorite, though Sports Illustrated predicted that Patterson would win in 15 rounds. James J. Braddock, Joe Walcott, Ezzard Charles, Rocky Marciano and Ingemar Johansson picked Patterson to win. The fight also carried a number of social implications. Liston’s connections with the mob were well known, and the NAACP was concerned about having to deal with Liston’s visibility as world champion; it had encouraged Patterson not to fight Liston, fearing that a Liston victory would tarnish the civil rights movement. Patterson also claimed that John F. Kennedy did not want him to fight Liston either. In the ring, Liston’s size and power proved too much for Patterson’s guile and agility and Patterson did not use his speed to his benefit. According to Sports Illustrated writer Gilbert Rogin, Patterson didn’t punch enough and frequently tried to clinch with Liston. Liston battered Patterson with body shots and then shortened up and connected with two double hooks high on the head. The result at the time was the 3rd fastest knockout in boxing history. After the fight questions were raised on whether or not the fight was fixed to set up a more lucrative rematch.

.

When Sonny Liston became the world champion he hoped his criminal past and unsavory reputation could be put behind him. However at a time of growing racial unrest, he was cast in the public imagination as the angry, dangerous black man, as a result he was not a popular champion. After his knockout of Patterson, Liston practiced the speech he was going to give when the crowds greeted him at the airport in his adopted hometown of Philadelphia. However Liston was disappointed that on his return there was no one there except for airline workers, a few reporters and photographers and a handful of public relations staff. He left Philadelphia after he won the title in part because he believed he was being harassed by the police. While driving through Fairmount Park which he had to drive to get from the gym to his home he was stopped for “driving too slow” through the park. As a result in 1963 he moved to Denver, where he announced, “I’d rather be a lamppost in Denver than the mayor of Philadelphia.” Patterson and Liston signed for a rematch, held on the evening of July 22, 1963, in Las Vegas, Nevada. This fight lasted four seconds longer than their first fight, with Liston once again knocking out Patterson in the first round.

Until Cassius Clay [Muhammad Ali's name at the time] who had won the light-heavyweight gold medal at the 1960 Rome Olympics and had great hand and foot speed came into the picture, Liston was the most feared man in the world and had a reputation as the “World’s Baddest Man.” Liston was a fighter many other heavyweights were reluctant to meet in the ring. For example, Henry Cooper said that if Cassius Clay won, he was interested in a title fight, but if Liston won, he was not going to get in the ring with him. Cooper’s manager Jim Wicks said, “We don’t even want to meet Liston walking down the same street.” Liston was an ex-con with ties to organized crime whose ominous, glowering demeanor was so central to his image that Esquire Magazine caused a controversy by posing him in a Santa Claus hat for its December 1963 cover.

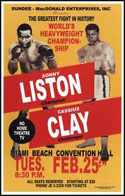

The contract for the Liston vs. Clay bout was signed in November 1963. Liston knew that Clay was the biggest money fight out there and virtually everyone expected him to easily dispatch the young upstart.

.

Liston’s title defense against Clay was held on February 25, 1964, in Miami Beach, Florida. Many of those watching were surprised to see that Liston was the significantly shorter man, and to knowledgeable observers it was also apparent that he was out of condition. The fight began with Clay showing a lot of movement, using a fast, effective jab and quick flurries of combinations. This made it difficult for Liston to score with his slower arm-speed and heavy punches. In the third round, Clay opened up his attack and hit Liston with several combinations, causing a bruise under Liston’s right eye and a cut under his left. During the fourth round, Clay coasted, keeping his distance. However, when he returned to his corner Clay started complaining that there was something burning in his eyes and that he could not see.

It has been theorized that a substance used to stop Liston’s cuts from bleeding (possibly Monsel’s solution) may have caused the irritation, but this has never been confirmed. In any case, Angelo Dundee rinsed Clay’s eyes with a sponge and pushed him off his stool to begin the fifth round, telling him to stay away from Liston.

.

Clay managed to survive the fifth round. By the sixth his sight had cleared, and he resumed control of the fight, landing combinations of punches seemingly at will. On his stool following the sixth round, Liston told his corner-men that he couldn’t continue, complaining of a shoulder injury. He failed to answer the bell for the seventh round and Clay was declared the winner by technical knockout.

Clay sprang to the center of the ring, did a victory jig and then quickly ran to the ropes to remind sportswriters that he had told them so all along. In a scene that has been rebroadcast countless times over the ensuing decades, Clay repeatedly yelled “I’m the greatest!” and “I shook up the world!” The day after the fight, Clay announced that he was changing his name to Cassius X, but then he adopted the name Muhammad Ali the following week.

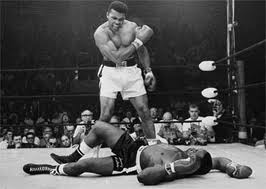

On May 25, 1965, Liston encountered Clay again, by then known as Muhammad Ali. The bout was originally scheduled for Boston, Massachusetts, but Ali, a week before the fight, was hospitalized with a hernia. The rescheduled match was held in the city of Lewiston, Maine.

.

Less than two minutes into the fight, while he was pulling away from Liston, Ali hit Liston with a punch which did not seem to have much weight behind it. However, Liston awkwardly went down, first lurching forward to the canvas then sprawling out onto his back, spread-eagled. In the total shambles that followed, referee Jersey Joe Walcott never counted over Liston and never made Ali go to a neutral corner, while Ali yelled hysterically at Liston, running around the ring, arms aloft. During this time Liston made an attempt to get back to his feet, before again rolling onto his back. After Liston finally got up, ringside boxing writer Nat Fleischer, who had no authority, informed Walcott that Liston had been on the canvas for over 10 seconds (during which time the fight had briefly resumed), and that the fight should be over. Walcott then waved the fight off even though he had never counted over Liston and had never made Ali go to a neutral corner, which meant the count in that fight is still at zero by the actual rules of boxing. The photograph of the suspicious knockdown of this fight is one of the most heavily promoted photos in the history of sports, and was even chosen as the cover of the Sports Illustrated special issue, “The Century’s Greatest Sports Photos”. Former champions Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis, and Gene Tunney, as well as Ali opponents George Chuvalo and Floyd Patterson, have all stated that they consider the fight to be a fake. The extent to which Liston’s alcohol use may have contributed to his surprisingly poor performances against Clay/Ali is not known; it was apparent Liston was out of condition for both fights.

After the second loss to Ali, Liston took a year off from boxing, returning in 1966 and 1967, winning four consecutive bouts in Sweden, co-promoted by former World Heavyweight Champion Ingemar Johansson. These knockout victories included one over Amos Johnson, who had recently defeated Britain’s Henry Cooper. In 1968, he won seven fights, all by knockout, including one in Mexico. America’s first look at Liston since the Ali rematch was in a nationally broadcast match with No. 5 ranked Henry Clark who he stopped in seven rounds. A 10-round decision over Billy Joiner in St. Louis continued the run of victories and Liston at 38 years old (but having the appearance of a man of 50) seemed on the verge of making a comeback to the big time, he talked of a fight with Joe Frazier, claiming “it’d be like shooting fish in a barrel”. But, in December, Liston was knocked out in the ninth round by Leotis Martin after dominating the majority of the fight, (Martin’s career ended after the fight because of a detached retina). Liston won his final fight against Chuck Wepner in June 1970. The referee stopped the bout in the 10th, with Wepner needing 57 stitches and having suffered a broken cheekbone and nose.

Liston was negotiating to fight George Chuvalo in Pittsburgh, when he was found dead by his wife in their Las Vegas home on January 5, 1971. She entered the premises and smelled a foul odor emanating from the main bedroom. She entered and saw Sonny slumped up against the bed, with a broken foot bench on the floor. The day of his death on his death certificate is December 30, 1970. Police estimated it by judging the number of milk bottles and newspapers at the front door. Following an investigation, Las Vegas police concluded that there were no signs of foul play. The cause of Liston’s death remains a mystery. The police declared it a heroin overdose. An autopsy revealed traces of morphine and codeine of a type produced by the breakdown of heroin in the body. His body was so decomposed that tests were inconclusive and officially, he died of lung congestion and heart failure.

Many, however, believe that the police investigation was a cover-up, because Liston was known to have a fear of needles. Liston was known to have refused to go on an exhibition tour of Europe when he was told he would have to get shots before he could travel overseas. Liston’s wife also reported that her husband would refuse basic medical care for common colds because of his aversion to needles. This, coupled with the fact that Liston was never known to be a substance abuser (besides heavy drinking), prompted rumors that he could have been murdered by some of his underworld contacts. Additionally, authorities could not locate any other drug paraphernalia that Liston presumably would have needed to inject the fatal dose, such as a spoon to cook the heroin or an appendage to wrap around his arm. This only added to the mystery surrounding his death. A friend of Liston’s told “Unsolved Mysteries” (An American TV program that uses a documentary format profiling real-life mysteries) that Liston had been in a car accident a few weeks prior to his death. Liston was hospitalized with minor injuries, and received intravenous medicine. This is believed to be the source of the puncture wound that authorities found upon discovering Liston’s body.

“Nick Tosches wrote in “The Devil and Sonny Liston.” “He rode a fast dark train from nowhere, and it dumped him from that falling-off place at the end of the line.” Liston is interred in Paradise Memorial Gardens in Las Vegas, Nevada. His headstone bears the simple epitaph “A Man.”

During his lifetime Liston acted in a number of films, the most famous being Harlow with Carroll Baker.

One of Sonny’s closest friends was Len Banker, who describes Liston as a regular kind of guy and negates most of what is said about Liston. In an interview by Gary James, Banker says “He liked to fish and hunt (Liston) although I never went fishing with him. He used to go out to Lake Meade. He was good with kids. He donated a lot of his equipment to the boys’ club here. He was a good family man. With his wife Geraldine, they adopted a little boy, Daniel, from Sweden, when he was a champion doing an exhibition in Europe. He was a good father”.

Liston was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, 1991 and inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame, 1990.

Boxing Record - won 50 (KO 39) + lost 4 (KO 3) + drawn 0 = 54 Fights

.

Sonny Liston - Trivia

- Was the favorite fighter of the famous Fab Four, the Beatles, and he appears on their “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” album cover.

- “Night Train” was his favorite song.

- In Michael Mann’s Ali, Liston was portrayed by famous boxer Michael Bentt, with whom he shares a strong resemblance.

- Was 35-1 going into the first Ali fight..

- When he won the heavyweight title in 1962 at age 30, he had a daughter age 25. However, it turned out to be his stepdaughter, the daughter of his wife.

- He had no children of his own.

- Joe Louis rated Liston’s jab one of the best in boxing history.

- George Foreman was his sparring partner from 1969 to 1970.

- Made over $4,000,000 in his career.

- First heavyweight title challenger to earn a purse of $1,000,000.

- First World Heavyweight Boxing Champion banned from fighting in New York State by the New York Boxing Commission.

- Liston was the youngest heavyweight boxing champion to die (age 38).

- Survived by his wife Geraldine and a step-daughter.

- When Liston died, he was rated 7th in the world heavyweight rankings by Ring Magazine.

- Eddie Dooley, chairman of the New York Boxing Commission in the 1960s, said that as long as he was chairman of the commission Sonny Liston would never be granted a license to box in New York State.

- Liston claimed he was born in 1932, yet his rap sheet for his 1950 arrest for armed robbery listed his age as 22, making him born in 1928.

- Personal Quotes - Liston on his age: “I’m like Jack Benny, I never tell my age.”

.